- OFFICIAL WEBSITE OF AWARD WINNING WRITER -

RUSS WOODY

If you have time to waste,

this is the place to do it!

Tuesdays with Ted

An uplifting, heartbreaking, occasionally funny story about an old man with ALS, a sitcom, its star

and just enough time for a son to say goodbye

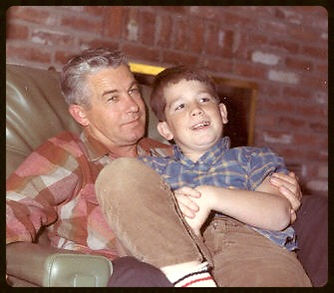

HE 17 MONTHS I got to spend with my dad were, of course, fraught with difficulties, but they were, as well, chockablock with humor, since—as nearly any comedy writer will tell you—in the midst of great hardship, there is always funny. Though at the time, I didn’t think of the experience as an “honor,” as I look back, I realize that it was an honor of the highest order.

M

y dad (Woody) was diagnosed in the spring of 2001 with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS—Lou Gehrig’s disease—a fatal illness that gradually paralyzes its victim. Three days after his diagnosis, my mother died unexpectedly from complications of a bleeding ulcer. They’d been married 58 years.

Woody had always been easy going, gregarious, fun to be with; qualities that perhaps fueled my mother’s emotional insecurities. Insecurities that, in turn, drove her to feel threatened by his relationship with just about everyone, including me. So, after high school, I learned to stay away. And that’s what would be both so sweet and heartbreaking about the months that were to follow his diagnosis—I was finally able to spend all the time I wanted with my dad, but time was something we had little of. As a result, the months we spent together presented a rarified window, a sliver of light that flashed across the sky like the wing of a Blue Angel. I couldn’t stop the spinning clock, couldn’t steal more time, but I could clutch the moments we had and pull them close.

T

The Becker Episode about Woody

4 minutes

Though his life was ending—with the death of my mother—it was also, it must be said, just beginning. After he moved from his house in Pahrump, Nevada, to a house in Los Angeles a few blocks from my wife and me and our two sons, Henry and Joe, his life changed dramatically: He became friends with Ted Danson, was virtually adopted by the cast and crew of Becker and he became close to a number of my friends, many of whom are gay—an entirely new experience for him. He spent Thanksgiving at Marsha Mason’s house in New Mexico, had dinner with Shirley MacLaine, became an extra on J.A.G. and was the subject of an episode of Becker. For that, he was featured on Entertainment Tonight, E! Entertainment, in TV Guide and he was honored by the Muscular Dystrophy Association at a black tie dinner in Beverly Hills.

Most important, he became a part of his grandsons’ lives. After the move, he bought bunk beds for the middle bedroom of his house, so that they could stay at Grampa’s on the weekends. Saturday and Sunday mornings they were greeted with pancakes, bacon and plenty of syrup. Then, while he still had strength in his arms and legs, he built for Henry and Joe a massive fort on stilts in his back yard. Later he cleared his living room of furniture to construct for them an incredible swooping, winding, looping slot car track. When I complained that he’d never built anything like that for me when I was little, he laughed and said, “Tough.” Henry and Joe breathed light into his life; they alone stole focus from the dark horizon that he faced.

To be with him, to be with a parent, while they are dying, is one of the most human of experiences. It is what we are supposed to do. And while those months were difficult in a myriad of ways, they were also the richest and most rewarding of my life. Though at the time, I didn’t think of the experience as an “honor,” as I look back, I realize that it was an honor of the highest order.